Tackling Misinformation with the Ledger of Record

This is the third article of a 3-part series on my reflections from Smart Contract Summit 2021. Check out the first and second articles.

The world’s information supply chain is broken. Balaji Srinivasan, General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz and former CTO of Coinbase, astutely maps out this supply chain starting from the explosion of big data, both peer-reviewed and unverifiable. The festering of distorted information cascades down the chain of publishing research, news reporting and government regulation. We have experienced tangible and adverse ramifications of these bad informational feeds throughout the tumultuous periods of COVID-19 and election seasons.

Misinformation is defined as false or inaccurate information, regardless of any intention to mislead. Disinformation is a subset of misinformation, with the added attribute of deliberate and at times, nefarious motivations.

Many have pinned the blame on social media platforms, the central medium of information exchange in the Digital Age. While Facebook’s efforts to stymie the proliferation of misinformation with human fact-checkers, algorithms and the newly minted Oversight Board are laudable, there needs to be a greater tripartite collaboration among governments, private industry and consumers. Notably, the proposal of a blockchain-based ledger of record has the potential to radically revamp our information supply chain.

Information Supply Chain. [Source: Balaji Srinivasan, SmartCon 2021]

Information Supply Chain. [Source: Balaji Srinivasan, SmartCon 2021]

Combating disinformation from the top-down by governments and corporations may not be as effective and scalable as crowdsourcing.

Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) was passed in Parliament on Oct 2019, empowering the government to identify and stem the spread of falsehoods. POFMA has mainly been invoked for correction directions, requiring recipients to correct the falsehood accordingly, while very few disabling and access blocking orders, restricting Singaporean’s online access to the site in question, were meted out. POFMA is used only when public interest is at stake, proven to be effective in countering disinformation especially during COVID-19 and when racial or religious issues are involved. Nevertheless, detractors argue that such hard line legislative actions are more than necessary in “milder cases”, with an inadvertent effect of threatening free speech and political discourse. The area of contention is in demarcating the areas of “public interest”. Laws with punitive measures of arrests and imprisonment, such as the Digital Security Act in Bangladesh, receive harsh criticism for undermining freedom of speech. On the other hand, government inaction would invariably invite malicious actors to proliferate falsehoods unchecked. Perhaps top-down legislation is only best used for countering disinformation and not broadly, misinformation.

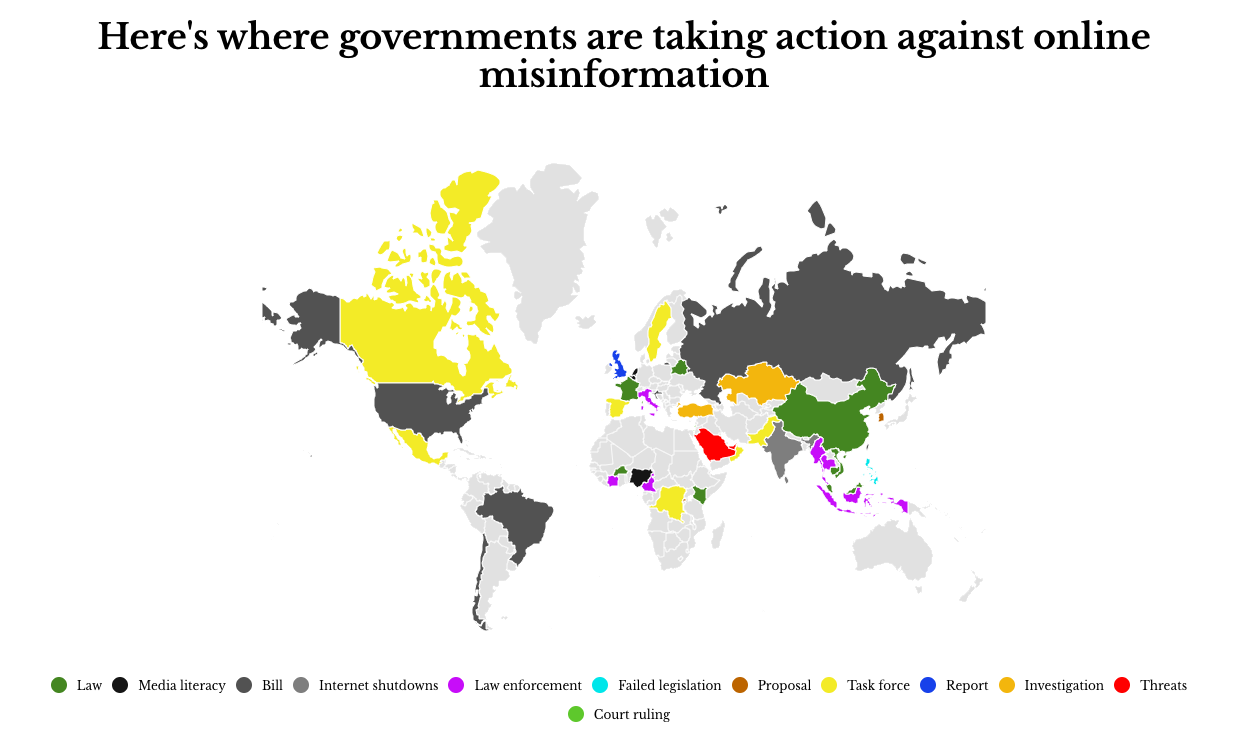

Geographical map depicting the types of anti-misinformation actions from governments. [Source: Poynter]

Geographical map depicting the types of anti-misinformation actions from governments. [Source: Poynter]

Facebook primarily works with independent third-party and non-partisan fact-checkers to review posts with misinformation. These fact-checkers from FullFact and PolitiFact are part of the International Fact Checking Network, adhereing to a set of principles dictating transparency of sources, funding, methodology and striving for open and honest corrections. Severe cases with widespread public attention are escalated to the Oversight Board, Facebook’s equivalent of the Supreme Court. The Oversight Board comprises a diverse spectrum of highly acclaimed individuals from across the world, including numerous academic professors, a former Prime Minister of Denmark and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. This form of adversarial fact checking serves to provide a more holistic and principled approach towards content management on Facebook, preserving the sanctity of freedom of expression.

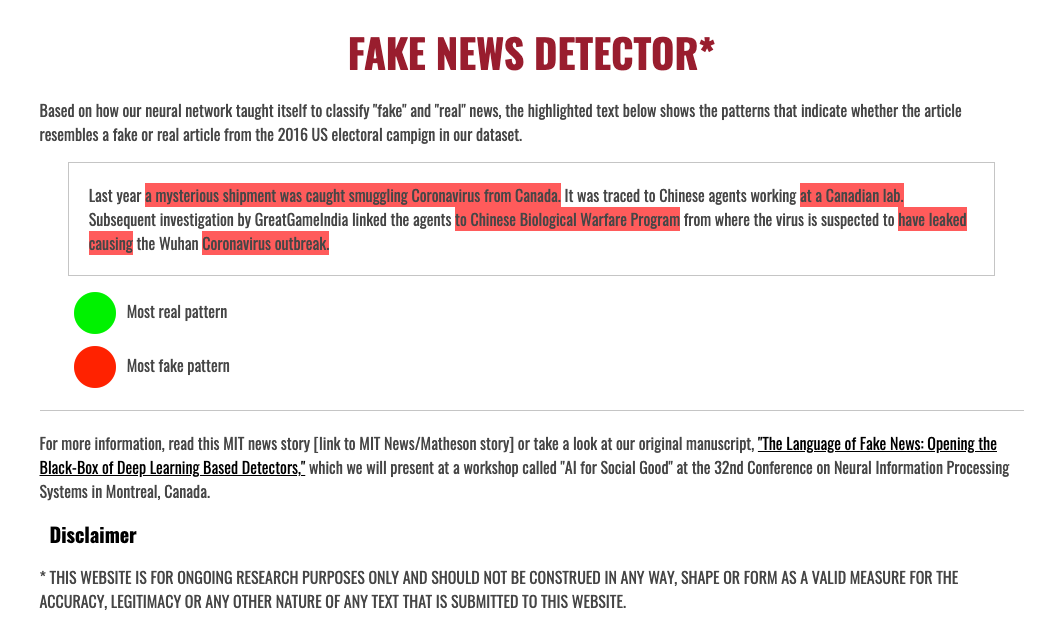

Apart from simply manual fact-checking, tech companies are utilizing market design mechanisms to disincentivize the spread of fake news, for instance Facebook marginalizing click baits with a revamp of their advertizing business model. Academics are also collaborating with industry partners to deploy natural language processing (NLP) models to detect fake news, ranging from sentiment analysis to MIT’s deep-learning based model (example shown below) and Harvard’s statistical approach for distinguishing human and machine generated texts.

Deep learning-based detector for fake news [Source: O’Brien N. et al, MIT]

Deep learning-based detector for fake news [Source: O’Brien N. et al, MIT]

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to please everyone. Decisions made by governments and social media platforms to take down a sensitive post are always susceptible to raising a furore amongst particular communities. Moreover, these top-down solutions, notwithstanding machine learning NLP models which have yet to prove their mettle, are not as scalable as perpetrators of disinformation. The impact is usually made after the damage is done. However, MIT Professor David Rand and URegina Professor Gordon Pennycook recently published a research study with results that trust ratings of media outlets by laypeople are well matched with those from professional fact-checkers. This indicates that crowdsourcing from the general public, with appropriate implementations on social media platforms and news outlets, is potentially reliable, scalable and effective in tackling misinformation. Ukraine’s StopFake project uses crowdsourcing to counter propaganda and promote media literacy standards.

A blockchain-based ledger of record unleashes the power of crowdsourcing.

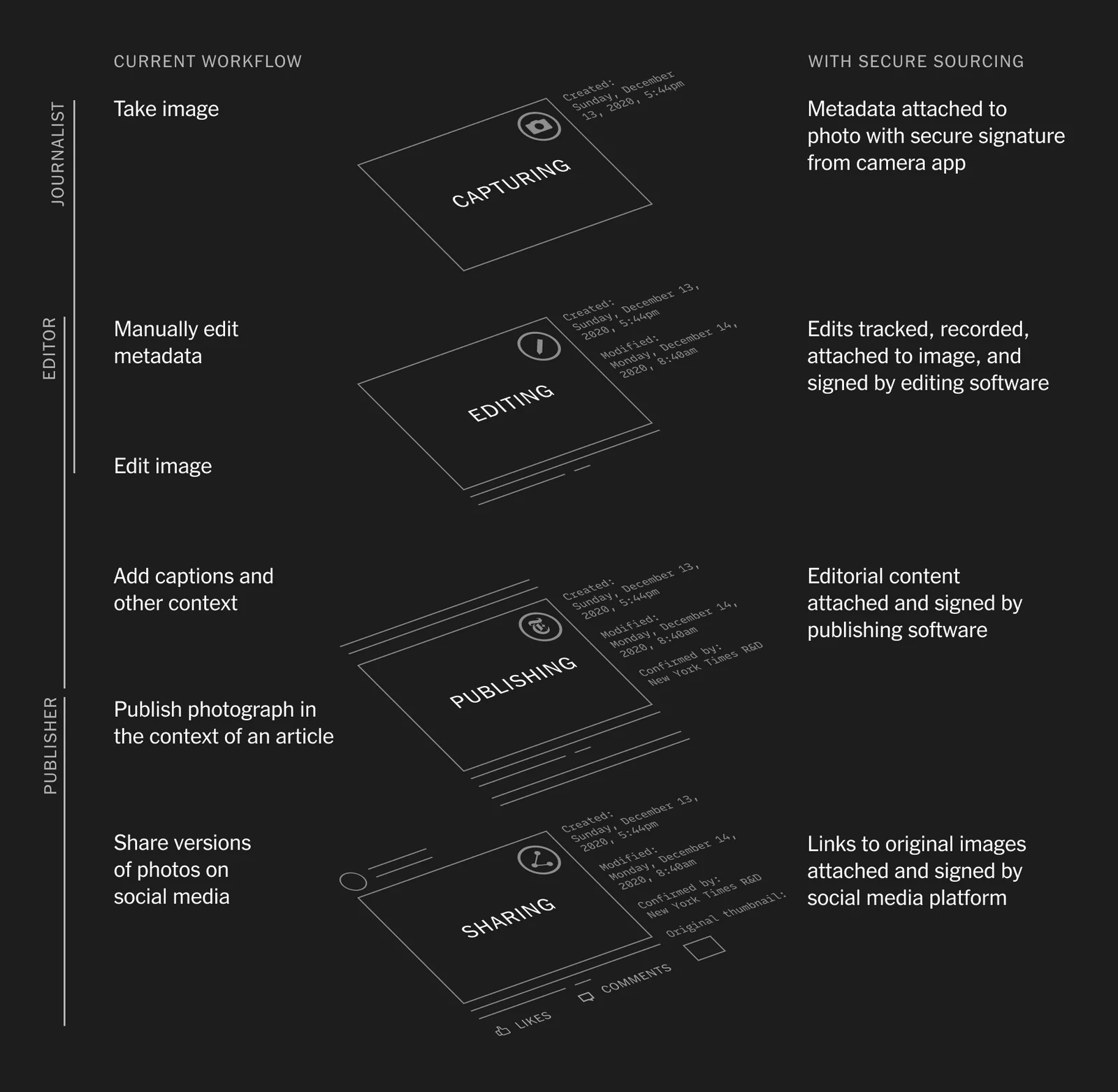

The latest iteration of the Harvard Berkman Klein Center Assembly Student Fellowship on Disinformation is a springboard for tripartite discussions and collaboration. The seminar with Professor James Mickens was one of the highlights. He discussed harnessing power of technology for external verification, where a digital history of metadata associated with images on news articles captures both source integrity and dynamic changes along the information supply chain. He proposed integrating widely adopted, existing tools for version control and digital signatures into a browser extension, but stopped short of blockchain. This brings to light the issues of maintaining anonymity and generating unique digital signatures for all devices.

In fact, the New York Times is collaborating with researchers from industry and academia to implement the aforementioned digital history, using secure sourcing and blockchain technology. Secure sourcing involves photographers, editors and publishers signing off at each stage of the news generation process. These cryptographically-secure signatures and hashes of image metadata are stored in a tamper-proof chain of provenance, accessible to the general public for review. The Content Authencity Initiative and Project Origin have drawn participation from Adobe, Twitter, BBC, CBC, Intel, Microsoft and Truepic. This proof-of-provenance chain ultimately establishes a reliable crowdsourced tool against misinformation.

Comparing secure sourcing with the traditional workflow or information supply chain [Source: NTY, Content Authenticity Initiative]

Comparing secure sourcing with the traditional workflow or information supply chain [Source: NTY, Content Authenticity Initiative]

Circling back to Balaji, he proposes a blockchain-based ledger of record to replace Reuters as a “globally accessible, machine-readable and decentralized wire service”. Extending beyond the digital history of images, Balaji opined that most news articles are essentially wrappers around numbers, be it sports around scores or public health around clinical trials data. Numerical facts on-chain are separated from off-chain narratives. Crypto oracles further expands their scope from proof-of-provenance to proof-of-location and proof-of-solvency. This novel information supply chain moves away from fiat information, where research is conducted with on-chain data. Reporting and regulation span across geographical boundaries, instead of irregular and inconsistent measures taken by one government. One pertinent application is a decentralized inflation dashboard to tackle widespread misinformation on inflation data, which has profound repurcussions on financial markets and monetary policy.

In light of the fact that such a ledger of record is still very much a work in progress, I implore my readers to fact-check this article. Check the links for corroboration, verify the sources and flag out dubious assumptions in the spirit of crowdsourcing.