Development Economics Meets Smart Contracts

This is the second article of a 3-part series on my reflections from Smart Contract Summit 2021. Check out the first and third articles.

During my college days, I was first exposed to the world of development economics as a research assistant under Professor Petra Todd - one of the key architects of conditional cash transfers (CCTs). Mexico’s Prospera has been successful in reducing poverty, increasing school enrollment and improving nutrition, indicating that said policy tool is effective in influencing consumption composition. Proponents identified four factors for success - having a well-defined target population, direct cash delivery, strong on-the-ground presence and robust evaluation studies. CCTs are currently implemented in more than 50 countries, helping millions of families to break out of the poverty cycle.

CCTs, however, are not the panaceas for the developing world. The widely-heralded Mexico model was recently terminated due to political pressure from the general electorate protesting against the program’s asymmetric benefits. Issues of contention include the exclusion of numerous families in poverty (due to strict target definitions), punitive sanctions for non-compliance and corruption from policy facilitators. Moreover, there are negative spillovers to non-beneficiaries such as commodity inflation in remote villages with a relatively high proportion of beneficiaries.

Development economics is concerned with understanding the comparative dynamics of economic growth across countries, and recommending best policy measures to improve the socio-economic conditions of developing and least developed countries.

Public-private partnerships are instrumental in development economics, especially when the private sector is more equipped to overcome the bureaucratic and technological hurdles faced by government programs. As part of an international development consulting group, I had the opportunity to collaborate with myAgro, an agricultural tech non-profit operating in Mali, Senegal and Tanzania. myAgro’s mobile layaway platform empowers farmers with a savings regime for better quality agricultural resources, coupled with training and mentorship programs. This innovative bottom-up approach has lifted more than 100,000 farmers out of poverty in 2020 alone, as well as promoted greater youth and female entrepreneurship.

Greater adoption of technology in development economics will only serve to enhance existing policy frameworks, and smart contracts are no exception. The adoption of smart contracts is more aligned with the bottom-up approach via the private sector, while central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) radically change top-down public policy tools.

myAgro farmers using the mobile layaway platform. [Source: Skoll Foundation]

myAgro farmers using the mobile layaway platform. [Source: Skoll Foundation]

The current outlook of Microfinance is bleak.

Microfinance is defined as a subset of financial services targeted towards the poor and unemployed, generally the underbanked and unbanked segments of society. Professor Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his pivotal efforts in pioneering the concept of microcredit. The overarching goals of microcredit are to fuel micro-businesses, reduce poverty and improve the living conditions of the developing world.

However, microcredit failed to keep its promise of “eradicating poverty in a generation” and “allowing the poor to be self-employed entrepreneurs en masse”. A recent study by World Bank economists, led by Robert Cull, employed the standard methodology of randomized control trials and concluded that the benefits of microcredit are modest at best. Firstly, the lack of purchasing power from the poor leads to muted demand increase and revenue inflow despite the rise in supply of goods and services from micro-businesses. Secondly, the interest rates on microloans are higher than average due to larger risks involved, thereby inducing greater debt burdens on barely fledgling entrepreneurs. Thirdly, it is challenging for these informal micro-businesses to transition into more productive and formal small-medium enterprises (SMEs). The cannibalization of customers and crowding-out of funding for incumbent SMEs inadvertently resulted in job loss and greater poverty. Fourthly, commercial microcredit still requires subsidies due to the lack of profitability, and a pure profit-driven approach leads to fraud and excessive lending in an unregulated environment. Commerical microcredit does not reach the poorest.

A rehaul in the delivery mechanism of microcredit is paramount in tackling the existing limitations, shifting from traditional financial institutions to localized clusters of agent access points and mobile banking, exemplified in myAgro’s operating model. Microfinance also extends beyond microcredit to savings and insurance, both of which are equally important financial services to the unbanked.

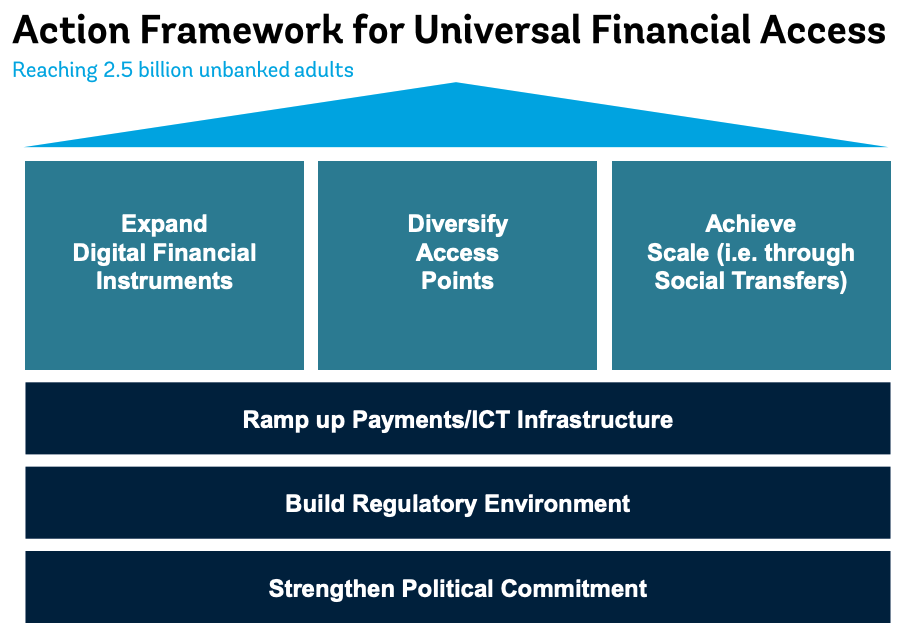

Framework for Universal Financial Access. [Source: World Bank Group]

Framework for Universal Financial Access. [Source: World Bank Group]

Smart Contracts come to the rescue of Microfinance via gaming NFTs, smart insurance and crowd-funding.

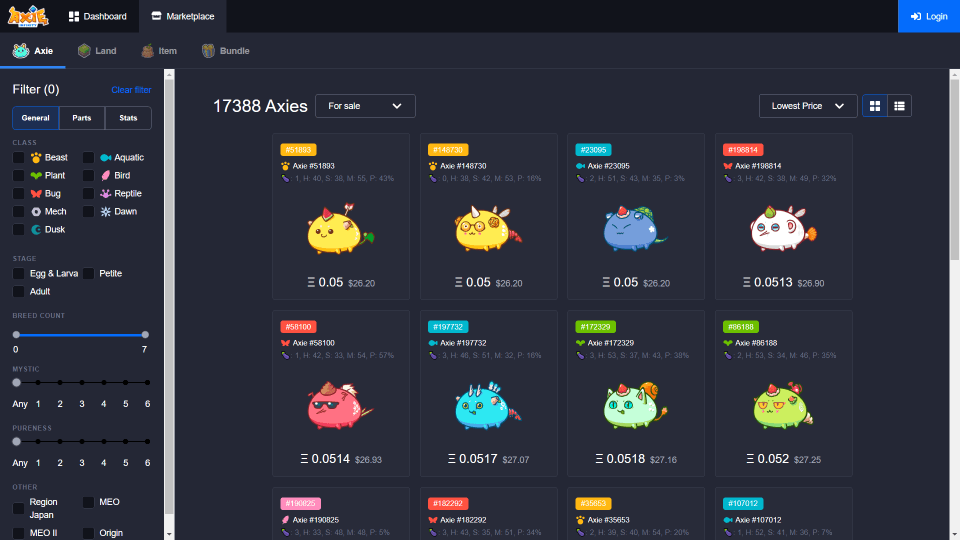

Folks in the NFT (non-fungible token) space will hardly miss Axie Infinity’s rapid rise to fame, with trading volume and sales exceeding $1 billion in less than a year. Axie infinity is a prime example of integrating NFTs (a form of smart contract) with gaming, building a Play-to-Earn model that has been touted by some as a universal basic income. Players primarily earn through selling unique Axie creatures as NFTs, speculate on rare Axies, trade Axie Infinity (AXS) or Smooth Love Potion (SLP) fungible tokens on exchanges and stake AXS governance tokens for yield generation. Players from all of walks of life in the Philippines relied on Axie Infinity as an alternative source of income amidst financial hardships induced by COVID-19.

The notion of a universal basic income (UBI) is not novel in the circle of development economists. In Good Economics for Hard Times, Nobel laureates Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo argued for an ultra UBI (UUBI) for the poorest. RCTs conducted in Kenya indicated that UUBIs do not induce laziness, contrary to the income effects of traditional UBI. Government debt burdens can be further reduced using self-selection mechanisms like visiting ATMs weekly to benefit from the payouts. Here, Axie Infinity offers a potentially efficient bottom-up approach to UUBIs when paired with appropriate government support and regulation. Upcoming NFT games include Guild of Guardians and Aavegotchi.

Marketplace for Axies NFTs in Axie Infinity. [Source: Trust Wallet]

Marketplace for Axies NFTs in Axie Infinity. [Source: Trust Wallet]

Climate change disproportionately affects developing countries, where higher frequencies of extreme weather, both droughts and floods, destroy harvests and stifle crop growth. Only 3% of farmers in Kenya have access to formal crop insurance as hedges against these unpredictable weather events. Traditional insurance companies are unwilling to risk extending services to farmers in developing countries due to difficulties in ascertaining risk profiles, validating claims and administrating payouts. Therefore, the innovation of smart contracts for crop insurance fills the market gap due to a lack of robust legal institutions and trust issues with insurance companies. Arbol’s smart contracts provide accessible and affordable crop insurance to the poor, ensuring timely and secure payouts. Google Cloud’s smart contract platform further enables developers to design a suite of blockchain-based insurance beyond the agriculture industry.

The market for crowd-funding in the developing world is projected to be worth $96 billion by 2025, providing another avenue of capital access for entrepreneurs. Slow adoption of crowd-funding in developing countries is due to a poor regulatory environment and barriers to payment by main platform players. One of the world’s largest crowd-funding platforms, Kickstarter, has a slew of guidelines and unique payment processors not readily available in developing countries. Once again, smart contracts have the opportunity to serve developing markets, for instance, with Tecra Space’s blockchain-based crowd-funding platform.

Stablecoins hasten governments’ efforts to roll out Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs).

Switching gears from smart contracts and bottom-up initiatives, the rising popularity of stablecoins as a medium of exchange poses a potential threat to monetary authorities around the world. Stablecoins are essentially cryptocurrencies backed by reserve assets, collateralized with fiat currencies, commodities or other cryptocurrencies (pegged at a higher ratio due to volatilty). Other forms of stablecoins are algorithmically programmed with total supply mechanisms to fix a peg. These stablecoins seek to combine the highly desirable attribute of price stability in fiat currencies with the security and speed of cryptocurrencies. In an ideal scenario, these stablecoins are optimal platforms for financial inclusion, empowering the unbanked and underbanked with secure financial services, as well as lower transaction fees.

Nevertheless, stablecoins are private market mechanisms without government regulation. Currently, the market capitalization of the USD Coin is already more than $25 billion, with an estimated annualized trading volume of $16 trillion comparable to financial flows in mainstream platforms, albeit due to high velocity. Hence, governments have yet another impetus to speed up research in CBDCs, achieving the same benefits from stablecoins while maintaining monetary sovereignty.

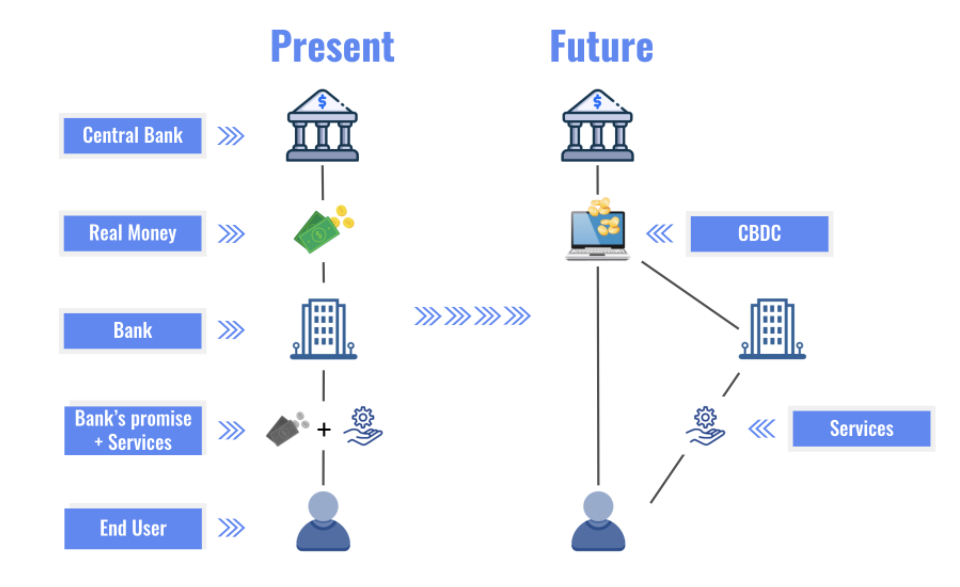

CBDCs are defined as a digital complement to cash backed by a central bank. They are not necessarily required to employ distributed ledger technology and smart contract capabilities although most beta versions do. The central bank aims to set base operating rules and system invariances (e.g. prevent programmability inducing inflation in base currency) to CBDCs, which can be a hybrid of wholesale and retail approaches. Wholesale CBDCs facilitate inter-bank transactions and electronic bank reserves in the central bank; retail CBDCs are digital cash made available to the public for consumption of goods and services. Hybrid CBDCs prevent disintermediation by having the central bank leverage on existing commercial banking infrastructure to provide services for corporations and citizens.

The impact of CBDCs on the current financial system. [Source: Daml]

The impact of CBDCs on the current financial system. [Source: Daml]

China is at the forefront of CBDCs with over $5.3 billion of transactions cleared with the digital yuan, or more formally the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP). The digital yuan is legal tender, non-interest bearing and has controllable anonymity. While China’s rollout of the digital yuan is viewed as a method of countering the (occasionally weaponized) international SWIFT system based on the USD as the world’s reserve currency, it does not discount the value CBDCs bring to faster and cheaper cross-border payments, as well as greater transparency in foreign aid. CDBCs also provide central banks with accurate information to track various economic indicators, allowing real-time calibration of monetary tools in different economic climates. Recent developments for CBDCs by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank spur healthy competition for greater financial digitalization and inclusion.

Public-Private Partnerships have been and will continue to undergird the future of Development Economics.

Taking into account the long runway required for CBDCs to be implemented at scale, the near-term solution is for governments to better engage the private sector by establishing an expert advisory board. This board serves to both lend expertise and provide perspectives fron the private sector when public agencies attempt to enact regulations in the fast-changing world of smart contracts and stablecoins. Ultimately, the efficacies of development policies depend on the balance struck between facilitating and regulating the free-market innovation machine.