The Superpower Battle in Semiconductors & Renewables

The US-China rivalry is heating up. Harsh words were traded between Blinken and Wang in Anchorage, and the G7 released a joint statement urging China to “respect human rights and fundamental freedoms”. Incursions into sovereign airspaces and territorial waters are becoming the norm. Is the world certainly headed towards a new Cold War? I beg to differ. Political tension will continue to simmer but intricate global economic interdependencies are effective deterrents to an all-out war.

My conversations with Moiz Jehangir, winner of the UPenn Norman D. Palmer Prize for Best Thesis in International Relations, have been enlightening. Recent political developments have led to the revival of realism and power-based approaches to international relations.

The balance of power (BoP) theory posits that state behaviour is determined by the existing distribution of power and peace achieved only with balance in the international system. On the other hand, the power transition theory (PTT) emphasizes dissatisfaction levels and the need for rising powers to embrace the status quo to avoid conflicts. However, both theories are heavily focused on the outcomes of power - military and economic.

In “How Oil Twists the Hegemon’s Arm”, Felicia Grey alludes to the notion that inputs to power matter more in understanding state diplomacy, or lack thereof. China’s largest imports in 2020, ranked by value, are integrated circuits and crude oil. With the rise of the Digital Age and impending perils of climate change, the semiconductors and renewables industries are mission critical resources for any global power. A preliminary analysis indicates an American victory in semiconductors and a Chinese stronghold in renewables.

1. The Semiconductors supply chain is globally intertwined and powers our everyday life.

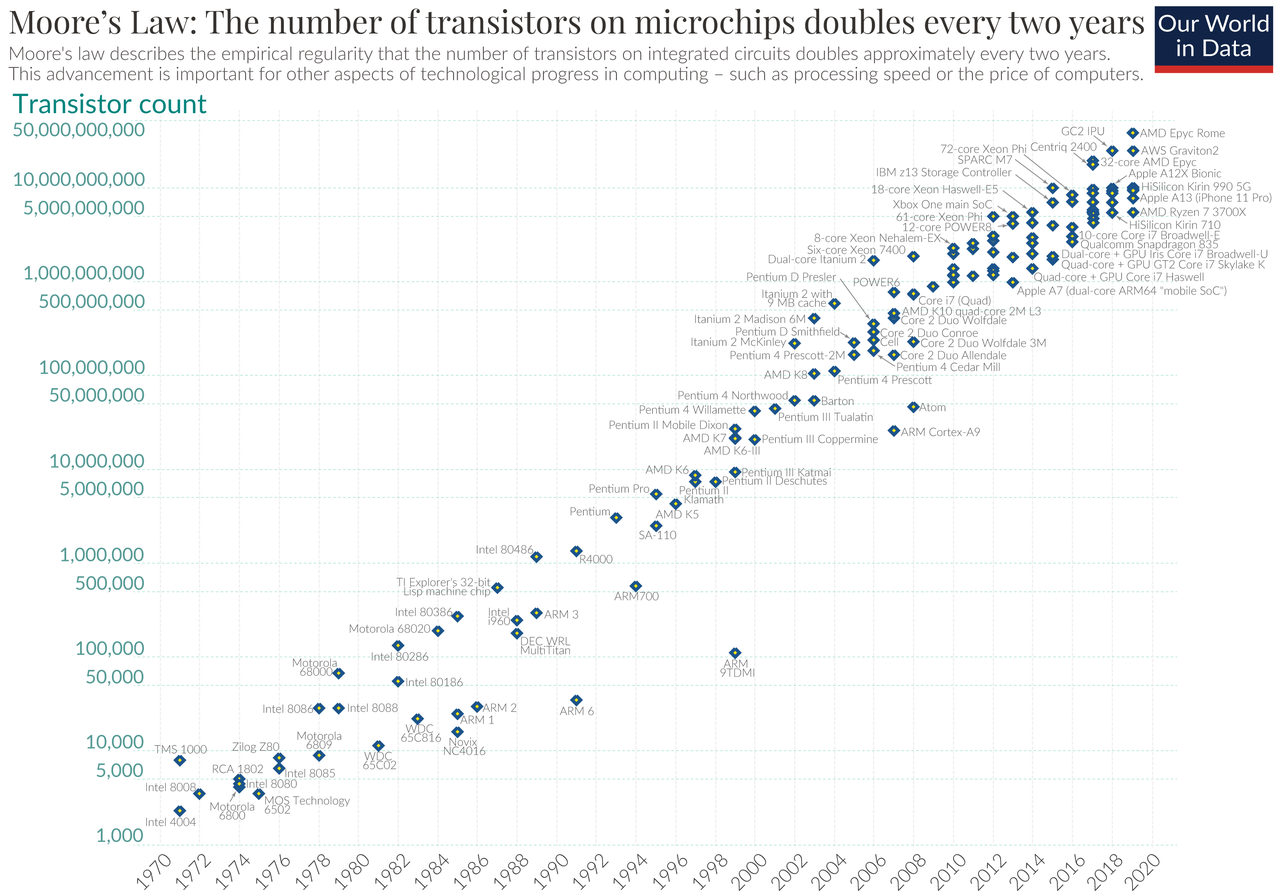

Semiconductors are to the Digital Revolution as steam engines are to the Industrial Revolution. The most advanced semiconductors today have billions of transistors packed onto a small piece of silicon, powering virtually all industries ranging from smartphones and medical equipment to artificial intelligence (AI) and automotive. Technological advancements have generally kept up with Moore’s Law - the doubling of transistors in integrated circuits every 2 years. Unfortunately, the current achievement of reducing transistor gate sizes to 5nm is reaching the natural limit, a portent of Moore’s end. In other words, the marginal cost of capital expenditure for a unit improvement in processing power is potentially exponential.

Number of transistors on ICs and Moore’s Law. [Source: Our World in Data]

Number of transistors on ICs and Moore’s Law. [Source: Our World in Data]

In the AI space, infrastructure for cloud-based end markets in big data training and real-time inference are projected to grow at a 27.3% compounded annual growth rate to $80 billion by 2026. Training relies on traditional microprocessors (CPUs / GPUs), field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) and inference on application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs). Apart from traditional dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips, the demands of AI infrastructure extend to high bandwidth memory chips, non-volatile memory chips and capacity for on-chip memory. The automotive industry is another network-based end market with strong tailwinds for semiconductors. The automotive chip market is projected to triple by 2030, with autonomous driving and inter-vehicle connectivity boosting demand for domain control units.

With the value proposition of semiconductors clearly indisputable, it is now easy to surmise that technological prowess and commerical access to semiconductors are instrumental to economic growth. The supply chain is highly globalized where a typical production process spans across more than 5 countries and has a 100 days throughput time. Conventionally, it starts with substrate and wafer manufacturing, followed by integrated circuit design, wafer fabrication, assembly, package, testing and delivery to end clients. The nature of the complex supply chain and high capital expenditure creates a winner-takes-all (or most) environment where new entrants face insurmountable challenges to rival the incumbent in a short time.

![]() Semiconductors Supply Chain. [Source: Business Times Singapore]

Semiconductors Supply Chain. [Source: Business Times Singapore]

The US has a strategic advantage in Semiconductors.

Starting from the first stage, wafer manufacturing is mainly produced by companies in Japan and South Korea. American companies are leading players in the high value-add circuit design space such as fabless Qualcomm for smartphone system on chips, NVIDIA and AMD for graphics chips. Dutch ASML wields the exclusive expertise in extreme ultraviolet-lithography (EUV) necessary for the most advanced fine circuit printing. A single EUV machine comprises more than 100,000 parts and costs up to $120 million. Taiwanese TSMC is the world’s largest pure-play foundry, producing chips for Apple and upstream fabless chip designers. Integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) sit across the entire supply chain. CPUs and FPGAs are dominated by Intel, specialty chemicals chips by Japan and memory chips by Micron, Samsung and SK Hynix. Therefore, the US holds significant leverage in rallying domestic companies and allies for political purposes - evidenced by various effective chip sanctions on Chinese companies.

What is China’s game plan for Semiconductors?

While China is still behind the US alliance in CPUs, FPGAs and 5nm fabrication, the trade war has invariably boosted momentum and motivation in the domestic semiconductors industry. Yangtze Memory Technologies Co (YMTC) has been successful in manufacturing 64 and 128-layer NAND flash memory chips, albeit less superior compared to Micron’s 176-layer product. New Chinese semiconductor companies and chip plants are also implicitly required to have at least 30% of their production tools sourced from local vendors instead of traditionally relying on foreign imports. Notably, political commentators are reading between the lines with regard to China’s recent extensive crackdown on big tech companies in the social media, ride hailing, gaming and tuition domains. The hypothesis is an effective top-down reallocation of financial resources and talent from internet companies to hardware tech and semiconductors, transitioning from a founder-centric to state-centric ecosystem. Apart from China’s internal attempts to gain self-sufficiency in semiconductors, prolonged sanctions by the US government would face backlash from American chipmakers with more than a quarter of revenue sales attributed to China.

![]() Incumbent semiconductors players and their Chinese counterparts. [Source: Nikkei Asia]

Incumbent semiconductors players and their Chinese counterparts. [Source: Nikkei Asia]

2. Why is China pivoting to Renewables?

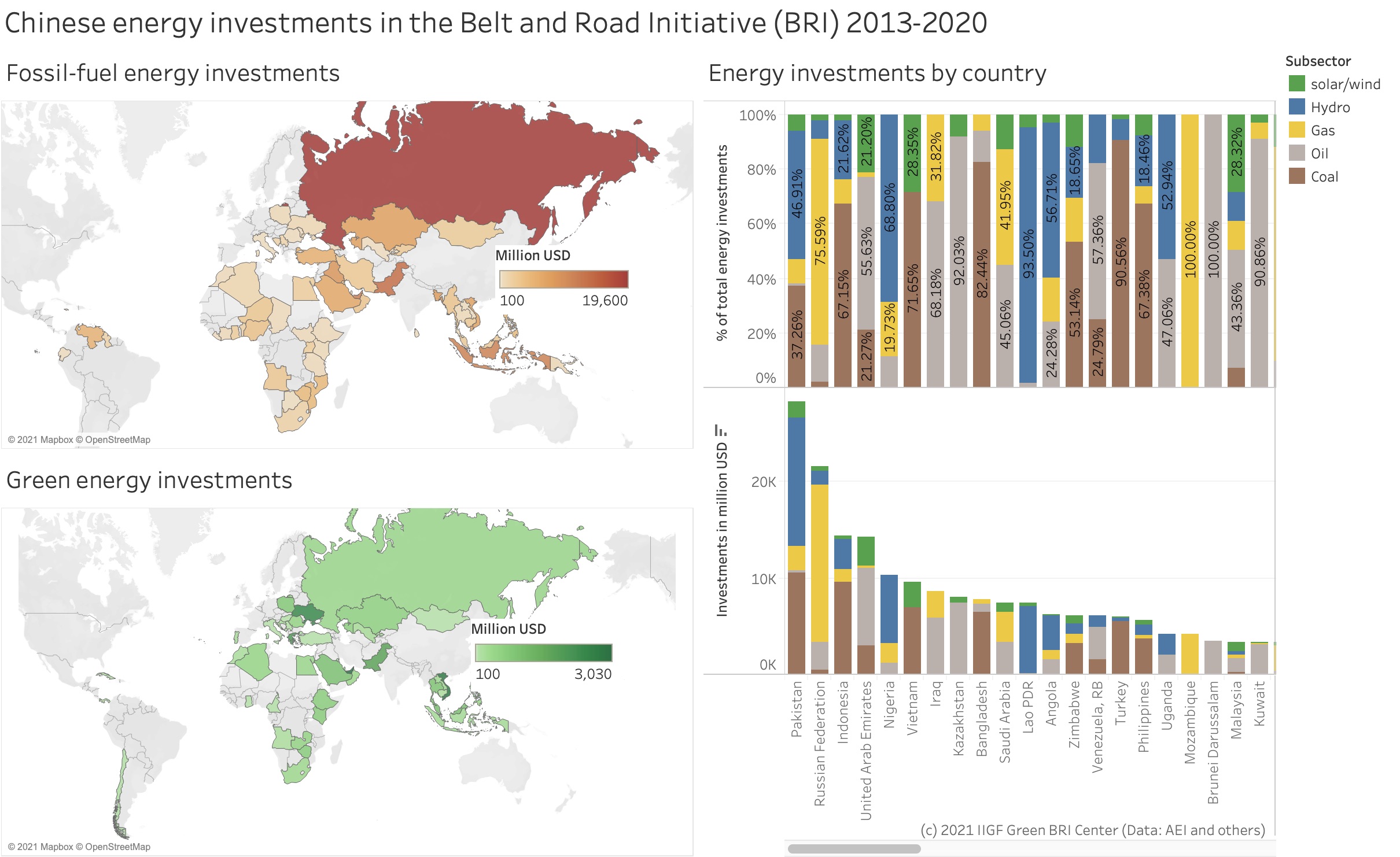

China’s domestic crude oil consumption stands at approximately 14,000 barrels/day, of which 70% is imported. The Middle East accounts for close to half of these imports and a majority of imported crude oil flows through the Straits of Malacca. Dubbed as the “Malacca Dilemma”, potential political conflicts in the straits would significantly cripple China’s crude oil supply, and in turn economic and military strength. Hence, China established the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to secure overland oil and gas pipelines amongst other infrastructural projects. The $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor secures oil supply from Gwadar Port (with strategic military importance as well) to the Kashgar economic zone, amounting to the highest energy investments in BRI. Other pipelines include those with Russia, Kazakhstan and Myanmar. The Sino-Iranian 25-year Strategic Cooperation Agreement also entails billions of investments into Iran’s oil and gas industries, plausibly in return for heavily discounted hydrocarbons. However, excessive reliance on crude oil is undesirable and China has been pivoting to renewables for energy self-sufficiency and less environmental pollution.

Belt and Road Initiative energy investments by country. [Source: IIGF BRI Green Center]

Belt and Road Initiative energy investments by country. [Source: IIGF BRI Green Center]

China is poised to be the “Saudi Arabia of Renewables”.

BRI investments into renewables exceeded that of fossil fuels for the first time in 2020, signalling China’s commitment to renewables. China currently holds almost of a third of both the world’s wind and solar energy capacities, at 221 GW and 205 GW respectively. This capacity is more than twice that of the next largest player (US) at 96 GW and 76 GW.

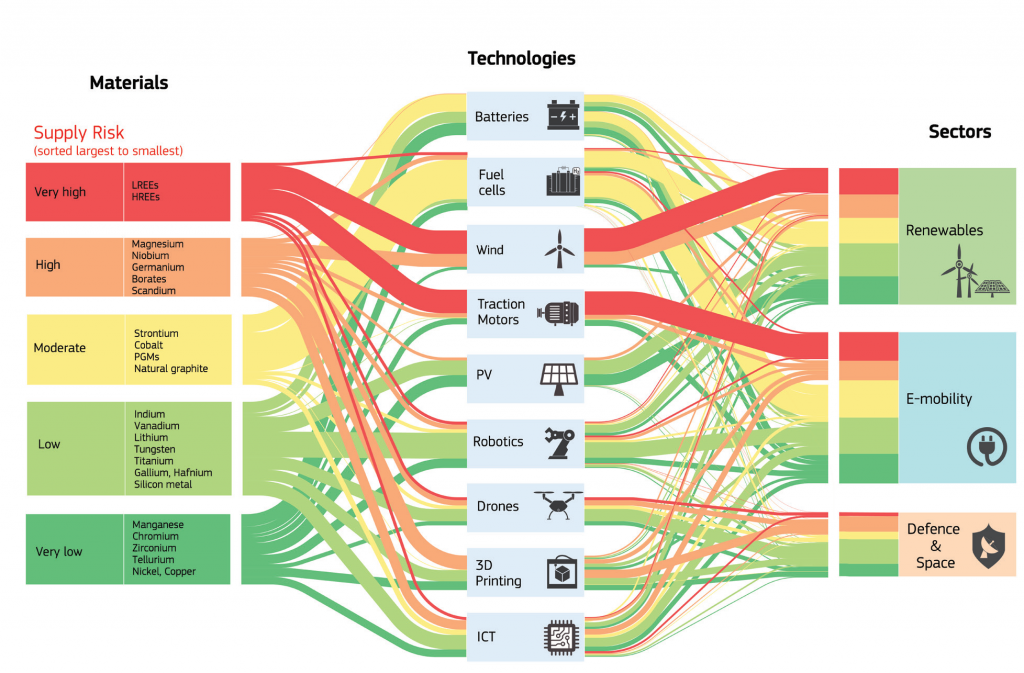

More importantly, China dominates the supply chain for renewables via domestic endowments and strategic “energy alliances”. In 2017, China accounted for 81% of the world’s rare earths production and 80% of all US rare earths imports. These rare earths are necessary materials for critical military hardware (GPS navigation, laser targeting, weapons, fibre optics) and renewables infrastructure (solar cells, batteries). Chinese companies have a majority stake in the DRC’s cobalt production, making up 70% of global production. Tianqi Lithium’s strategic investments in the Argentina-Bolivia-Chile Lithium Triangle secured more than half of the world’s lithium supply. It is no surprise that China produces 80% of the world’s lithium-ion output with 150 giga factories by 2030 (compared to EU’s 17 and US’s 10), powering the future of electric vehicles. The victor of the renewables battle is leaning towards China.

Supply risks and applications of rare earths. [Source: European Commission, Joint Research Center]

Supply risks and applications of rare earths. [Source: European Commission, Joint Research Center]

Is bipolarization inevitable?

Circling back to Felicia Grey, the peculiar relationship between US and Saudi Arabia exemplifies how nations of conflicting societal values can have functional and flourishing economic cooperation. Strong economic interdependency between the US and China provides an opportunity for the business communities to diffuse political tension. The clarion call for a concerted global effort against climate change galvanizes industries and academics across borders. Perhaps it is time for world leaders to transition from passive dialogues to active collaboration. We need to avoid a bifurcated global supply chain of semiconductors and renewables.